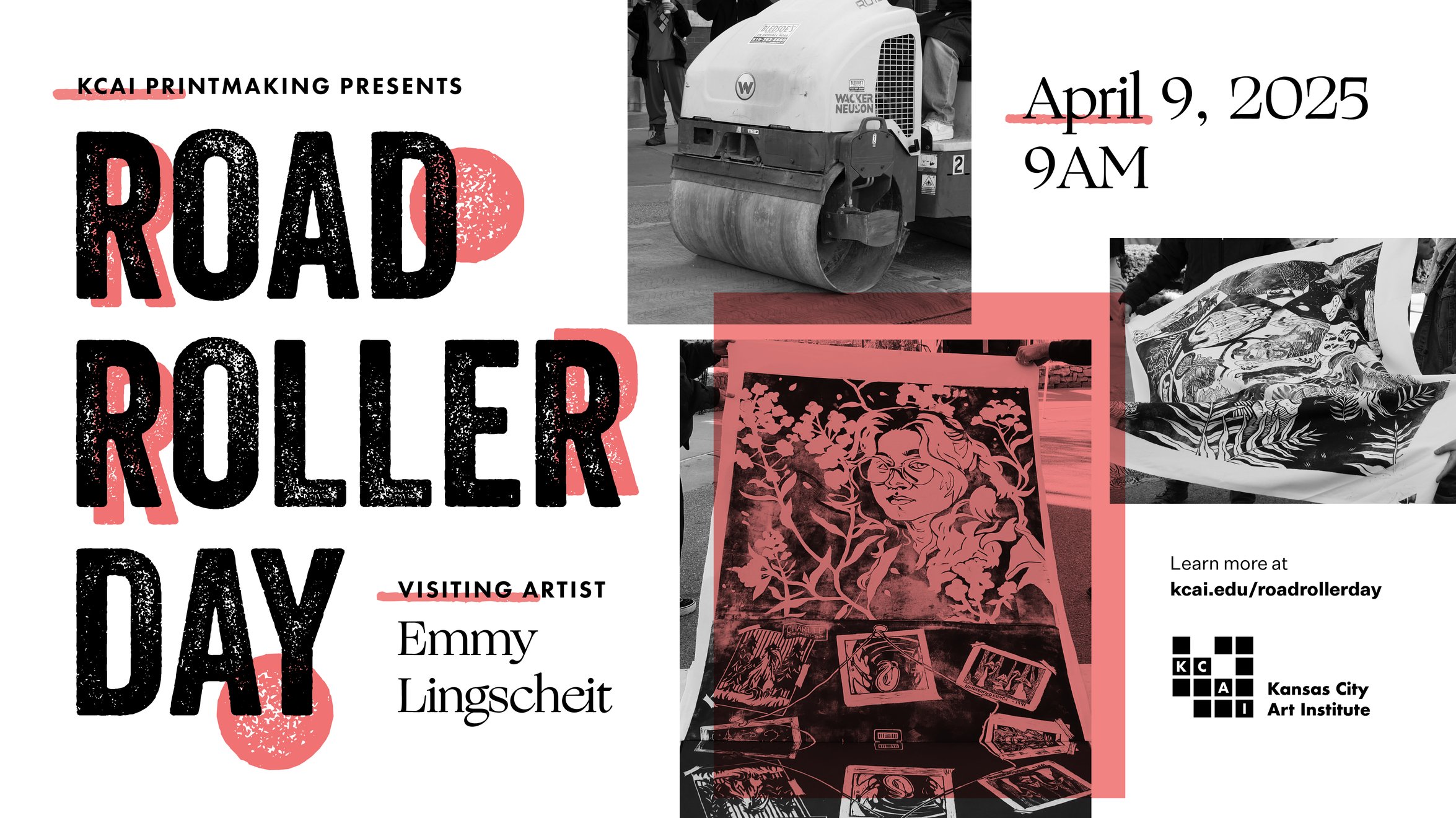

Road Roller Day 2025: A Public Event to Witness Giant Prints in the Making at KCAI

03.05.2025

The public Road Roller Day 2025 event will be held on Wednesday, April 9th, at Rowland Commons on the Kansas City Art Institute campus. The event will run from 9:00 AM to 4:00 PM, offering a full day to watch the process.

On A Roll

On Road Roller Day, KCAI's Printmaking department uses heavy construction equipment to create large-scale woodblock prints, with designs specially crafted for the event.

So, who typically enjoys witnessing this process in person?

"Children," says Miguel Rivera, Chair and Associate Professor of Printmaking at the Kansas City Art Institute.

"The indentations on the block, the decisions made, and seeing the mirror image emerge is something kids have forgotten. We're so used to computers and phones, where everything is superficial—no pun intended. "

"But here, the surface is actually treated in depth, and you can see the embossing of the image coming to life. It's as honest as one can be when making a mark by hand. There's something magical about pulling that print,” Rivera says.

A Kind of Excavation

KCAI Printmaking is excited to welcome Emmy Lingscheit as the Road Roller 2025 Visiting Artist. On Wednesday, April 2nd at 8:30 AM, Lingscheit will give a lecture in Epperson Auditorium before beginning work with students on the project. The public is invited to attend and learn more about her approach to printmaking and artistic background.

Rivera says, “Amy’s work focuses on using a lot of negative space, which is different from how a lot of students and faculty typically approach their art. We often feel the need to fill every inch of the surface, but Amy works in a more free-flowing, natural way. That’s one of the reasons we decided to invite her.”

The lecture will also introduce the theme for Road Roller 2025: Subterranea/Underground. From April 2nd to April 8th, students will create and carve 4x4 ft block panels, drawing inspiration from this theme. Lingscheit will work in tandem with students, sharing how she would approach certain images or carving styles by referencing samples of things that she has previously done.

Lingscheit writes, “I find the action of carving a relief block to be a kind of excavation, paralleling the acts of excavation performed by our non-human kin, and by scientists working to better understand our past and future on this planet.”

She envisions a project where each participant carves and prints an image that stands alone yet also contributes to an immersive paste-up installation. This will be accomplished by spontaneously manipulating, cutting, and collaging prints on the wall. A shared groundline will visually unite these prints, while allowing participants the freedom to engage with the theme in their own unique ways. Together, they will create layered new worlds—above, below, and in between.

“The mutability and variance inherent in printmaking allows for potentially endless repetition and recombination of printed images – a hopeful nod to the continuity of the natural world even in ecologically grim times, and to the hyperconnectivity of systems and organisms,” she says.

“This adaptability is a celebration of the resilient Other, ecosystems both literal and symbolic, and the inherent queerness of nature.”

After the public Road Roller Day 2025 event on Wednesday, April 9th, the printed works will be displayed in Epperson Auditorium.

Image: Emmy Lingscheit, Subterranea II & III

Revealing the Legacy

The scale of the project and its public nature add an element of mystery—there’s always anticipation for the reveal. KCAI Printmaking faculty members often talk about how, under pressure, we can’t see what’s happening until it’s released. This creates a sense of expectation, like an oppressive secret that’s finally unveiled to an audience.

Started in 2007 by the then Interim Printmaking Department Chair and Professor Laura Crehuet Berman along with faculty member and alum Lloyd Patterson, Road Roller Day was created as a way to celebrate and share community within and beyond the Printmaking Department.

This coincided with the first year of the establishment of the KCAI Printmaking Department itself, which Berman spearheaded while serving as the program head for many years. By 2007, the Printmaking Program at KCAI had grown in size, scale, and impact, and the Road Roller Event was a way to combine these attributes in a collaborative, festival-style event that shared printmaking with a wider community.

The timing of the event is also intentional—with the weather hopefully not too cold and not too hot—working outside the building but also outside of comfort zones. In the studio, students can adjust the pressure to thousands of pounds per square inch. But with the road roller, they have a set pressure, meaning drivers must make multiple passes to achieve the desired effect.

Rivera says, “We take turns. We have had students who don’t have a license, but, you know, if I'm there, we're good. They can drive it.”

The ultimate result will be a multi-panel print, with the expectation that the segments fit together like a puzzle to create a larger print. The public is also invited to bring non-traditional artifacts to print on—things like hats, shirts, or even a banana—anything that will hold ink—for an impromptu press by the road roller.

Effort and Impact

The public event will be the culmination of days worth of work by students and faculty. A typical visiting artist might put in 3-4 hours a day during the lead-up week, with students doing even more. And its physical work, carving much of it by hand.

The public event is the culmination of days of hard work by students and faculty. Typically, a visiting artist might spend 3-4 hours a day working during the lead-up week, with students dedicating even more time. And it’s mostly physical work, with contributors carving by hand.

“I would say three out of four students enjoy it,” Rivera says knowingly. “But we are allowing some use of the central shop CNC router to save time for certain parts where it makes sense.”

The focus, however, remains on the hands-on experience. Rivera highlights that for younger children, witnessing the process is crucial for their development, as it emphasizes the relationship between cause and effect—pressing and imprinting

"We noticed that students are losing that part of the brain that teaches learning through touch. Tactile experiences feed the brain for certain skills, and that part is missing,” Rivera says.

“So when they come here and see this relief block carved by hand and making something, you know, something really happens in our brain that wants to learn more about it.”